Inequality in education

What can be done to combat inequality in our educational system?

Does inequality in school begin at home or is the system itself to blame? Three UvA experts explain.

A new system

In October 2012, the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to Americans Alvin Roth and Lloyd Shapley "for the theory of stable allocations and the practice of market design.” That evening, a colleague of UvA professor Hessel Oosterbeek appeared on Dutch TV show De Wereld Draait Door to discuss the prize.

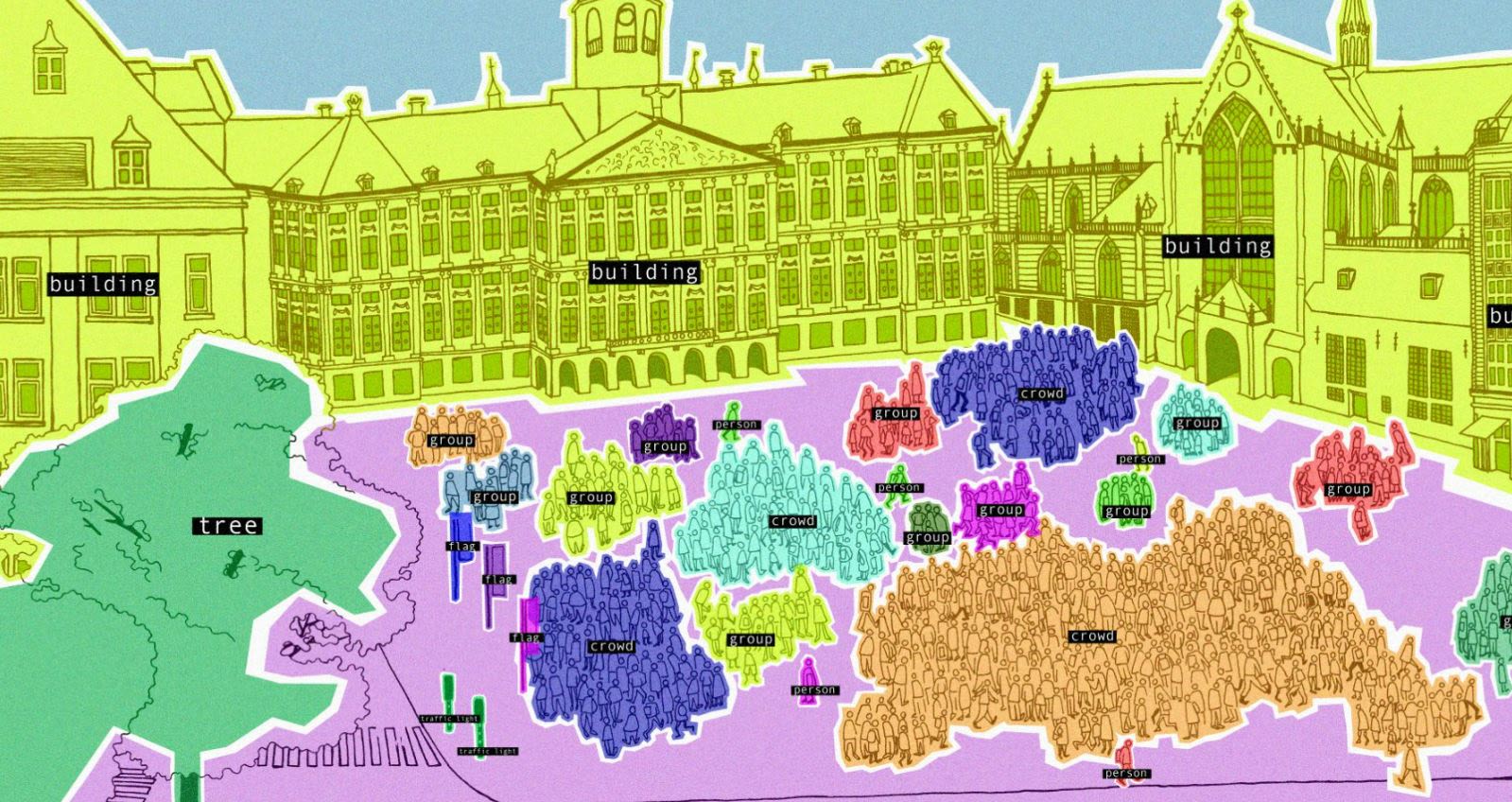

He mentioned how the Nobel laureates’ work on matching in markets where money was not involved could be usefully applied to the process of assigning students to secondary schools, and apparently someone from Amsterdam City Council was watching.

By 2015, the system proposed by Oosterbeek and his colleagues was in place and helping to decide where thousands of students would attend high school.

Oosterbeek: ‘You always hope your research has conclusions relevant to the real world, but it’s rare to see it have such an immediate and lasting effect as this'.

Enter the lottery

How it worked then: Students applied to one school, if it was oversubscribed a lottery was organised and, if they missed out, they could then only choose from those schools which still had places up for grabs.

Oosterbeek: ‘This meant a certain amount of strategic decision making was required when it came to popular schools. We conducted a study that showed that students from poorer neighbourhoods, already the most disadvantaged, were most likely to make a mistake in their strategy.’

How it works now: Students supply a ranked list of schools. Each student is given a lottery number and then placed in their highest ranked preference that still has places.

‘Strategy has been removed from the equation. You can be lucky or unlucky, but you can’t make a mistake. The new system makes it an entirely level playing field.’

Who is Hessel Oosterbeek?

Hessel Oosterbeek is Professor of Economics at the University of Amsterdam. His main research interests focus on the economics of education, development economics, and impact evaluation.

Pandemic home-schooling

Near the beginning of 2020, it was announced that schools across the Netherlands would be closed as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. Researchers working in the area of education worried that the consequences of school closures would be unequally distributed across children from different backgrounds.

Sociologist Thijs Bol was one such researcher. He immediately put together a Covid-related study looking at the extent to which parents were helping their children with home-schooling. The study identified big differences between socioeconomic groups.

The family you're born into

Bol: ‘Our work informed part of the national debate around school closures. Not just in terms of learning loss, but also in terms of inequality of learning loss. Suddenly our research became very practically usable in thinking about how to mitigate the negative effects of school closures.’

‘Children enter school and immediately begin to grow apart in terms of attainment and the question is ‘Why?’. While the initial reflex might be to look at the schools for answers, I believe we should be looking at the families as having at least as important a role.

People tend to think that it’s on their own merits that they rise or fall, but success is often owed to factors over which we have no influence, like the family we were born into.

'When we think about how our lives have turned out, we think about the actions we ourselves took, rather than the things we had no control over. Once people start to realise that, it allows for more empathy.'

Who is Thijs Bol?

Thijs Bol is an Associate Professor of Sociology in the Department of Sociology at the University of Amsterdam and is the academic coordinator of the Amsterdam Centre for Inequality Studies.

Jumping the tracks

Much of the research on inequality within the system of Dutch schools focuses on the selection and tracking processes. Educational scientist Louise Elffers focuses on this area in particular.

Elffers: ‘I focus on the design of our educational system and how it affects children’s school careers. In the Netherlands, we select students very early and place them in one of a large number of tracks. This immediately begins to affect their opportunities to learn, because we give them different content, different curricula, different standards, even different durations of education.’

‘I am in permanent dialogue with schools, teachers, counsellors and so on. I believe in proper two-way partnerships with schools, so I visit them, hold meetings, ask them what’s going on, and then base my research on what I hear from them. My focus is on the design of the entire schooling system, and, given the system, how we should be designing our procedures, for example when it comes to the tracking recommendation.’

'If we could design a new system on a blank sheet of paper, we would come up with something different, but we’ve had this system institutionalised for 100 years and we not going to re-invent it any time soon, so we have to work with what we’ve got.'

Who is Louise Elffers?

Louise Elffers is associate professor of Equity in Education in the Educational Sciences programme group at the UvA. Her work focuses on the design of education (systems) and the influence of that design on the school careers of young people with different educational and home backgrounds. The issue of equal opportunities and inequality in education is a common thread in her work.

Foto: Kirsten van Santen

Foto: Kirsten van Santen

What we need to improve

Oosterbeek: 'Each year we continue to advise the council about the selection procedure and make small tweaks to the system. We also sift through the data the system produces to see if we can glean insights into the issue of school segregation. It was long believed that residential segregation - people from different backgrounds living segregated from each other in different areas - was playing a role, but that appears not to be the case: people from different backgrounds living next to each other frequently go to different schools even when assigned to the same track. We need further data on what is causing that.'

Remove the human factor

Elffers: 'The selective procedure in our system has become much too dominant. We require teachers to identify very small differences between students and make very early predictions about their study potential based on those differences. When it comes to high stakes selection, such as assigning children to a secondary school track, we need to standardise more, and take out that human factor. Teachers often find that idea difficult, but it would mean so much more space for their pedagogical functions. Teachers actually do nothing but treat students unequally every day, giving each one the support they need, and that is what they should be focusing on.'

Disadvantaged families

Bol: 'Inequality becomes smaller when selection is delayed. It is particularly children from disadvantaged families who end up getting the school advice that is lower than their capability deserves. Examples from other countries show that when the age of tracking is delayed inequality of opportunity decreases. The UvA has been a strong contributor to research in this area and it is now being heavily debated at the policy level.'

No equality of outcome

Oosterbeek: 'Inequality exists but, ironically, the answer isn’t necessarily more equality. Equality of opportunity is what we should hope to achieve, but you can never guarantee equality of outcome. My feeling is: If you make rich parents unhappy enough you will end up with private schools, and nobody wants that. The philosophical ‘Veil of ignorance’ is all very well, we clearly want a system that gives the best to every child, but we must also accept what happens in the real world as soon as the veil is lifted.'

Unequal investment

Bol: 'If you want to mitigate inequalities, you need to give unequal investment. The children who aren’t being supported at home for whatever reason should be a priority, but what we see happening is the opposite: the current desperate shortage of teachers, for example, hits the children who were already behind the hardest. Those are the children we need to focus on the most.'

How do we ensure equal opportunities in society?

Researchers in the Social & Behavioural Sciences study this daily. Find highlighted research with new topics featured every week. Take a look at the dedicated page on inequality research at the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences.

Other stories about societal issues

Dealing with climate change

UvA-researchers are looking for ways to shape a greener future.

Research with impact

At UvA we do research that matters. Find our work on sustainable, fair, and healthy future here.

Hedy Tjin created the images for this article

Hedy Tjin is an Amsterdam-based illustrator and visual artist. Since graduating from the Academy of Arts in Utrecht, her work has developed a trademark recognisability. Whether it's murals, textile prints, illustrated books or a newspaper cover, Hedy is known for diverse expressions where her signature form stays constant; powerful colours expressing topics of societal value. Driven by a desire to use her work as a vehicle for inclusivity and openness, her vivid and radiant visuals aim to invite the audience to explore complex subjects in an inviting and new way. Combining an aesthetic that's alluring yet also highlighting important underlying messages is the ultimate goal to her.